The Ableist Legacy of Eugenics Research

A not so comprehensive look at the legacy of eugenics research in so-called Canada

The oppressive legacy of eugenics research underscores the urgent need for us to dismantle ableism embedded in both historical and contemporary practices of care. The following text critically examines the socio-historical impact of eugenics research and its harmful influence on public policy and societal attitudes toward disabled people. Understanding the historical role of research in perpetuating systemic inequalities can be a starting point for those who must evaluate the legacies of theory, praxis, and policy shaping their work. I will use eugenics research as a case study to explore how research framed disability as a societal problem that justifies segregation, sterilization, and institutionalization of disabled people.

In this letter, I am specifically looking at eugenics research and its implications for disabled people. In any context, intersectionality must be taken into account. The more intersecting marginalized identities a person holds, the more likely they are to be targeted by systemic discrimination. Eugenics is tied to immigration, slavery, imperialism, neoliberalism, etc. and is not isolated but works in tandem to oppress the many.

Research has historically been a powerful instrument to assert control over disabled people (Kattari et al., 2019). Eugenics research gained prominence in the late 19th and 20th centuries and legitimized ableist ideologies (McLaren, 1990). Coined by Sir Francis Galton in 1883, eugenics is defined as "the study of the agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations, either physically or mentally" (McLaren, 1990, p.15). Influenced by colonial notions of the superiority of certain races and abilities, eugenics research framed disabled people as inherently inferior (Stote, 2015). Rather than manipulating data, eugenics researchers constructed a framework to legitimize control over disabled people and provide scientific backing for harmful policies.

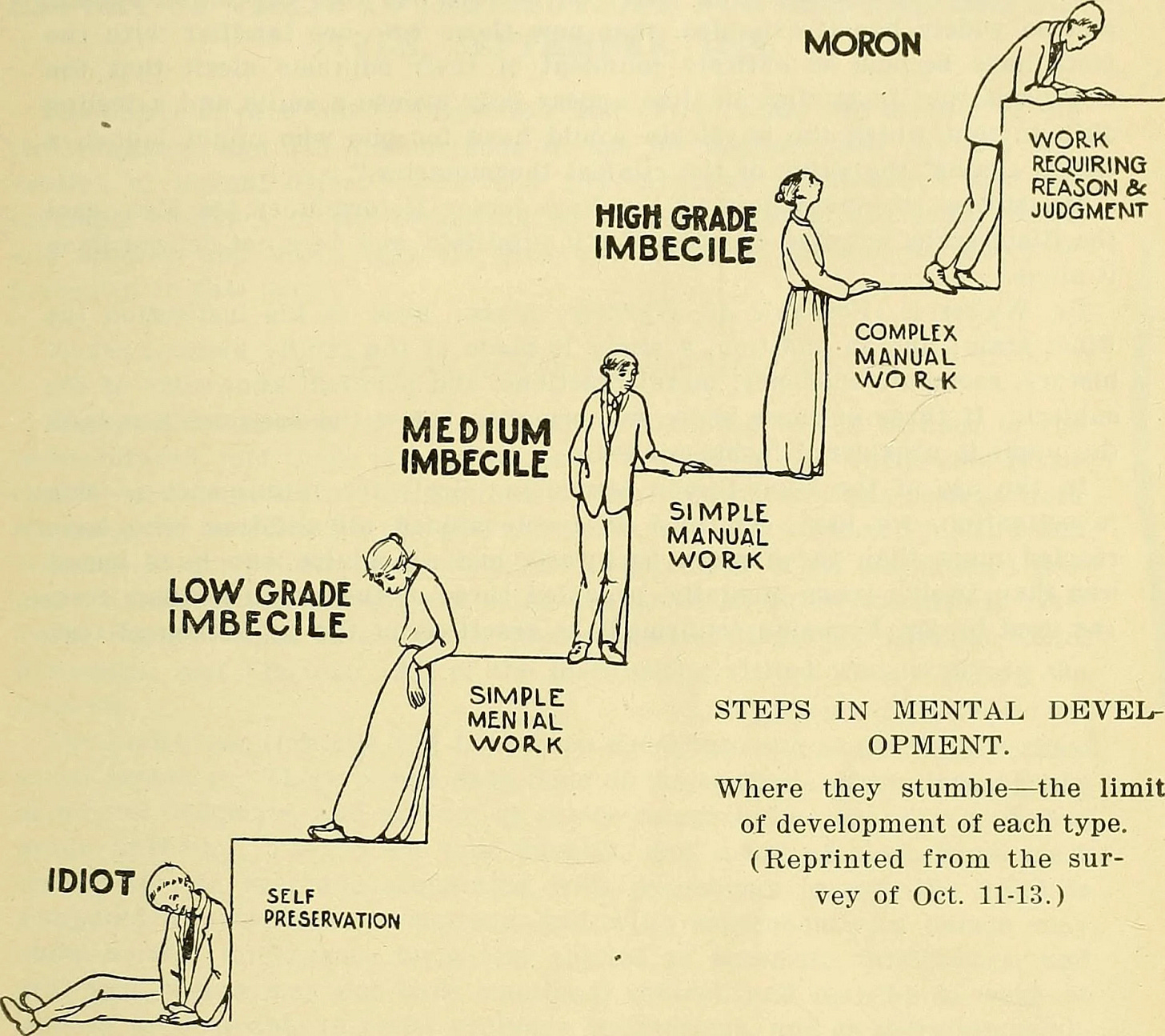

The work of Henry H. Goddard and Dr. Helen MacMurchy exemplifies how eugenics research was used to exert control over disabled populations and create harmful policies. Goddard's 1912 study on "Feeble-mindedness" used the Binet-Simon intelligence scale to label individuals as intellectually deficient, ranging from 'idiots' to 'morons' (Malacrida, 2015). MacMurchy's research advocated for controlling the reproduction of those she deemed "unfit" using segregation and sterilization to protect public health (McLaren, 1990). Their research was directly cited in the establishment of the Alberta Sterilization Act of 1928, which legalized forced sterilizations (McLaren, 1990). Over the next 5 decades, the Alberta Eugenics Board recommended 4,725 sterilizations that disproportionately targeted disabled women, teenagers, and Indigenous peoples (Fritsch et al., 2020). MacMurchy's research was instrumental in the widespread institutionalization of people with disabilities in so-called Canada (McLaren, 1990). Adopting the spatial exclusion of the mid-Victorian' idiot asylum,' her research endorsed the establishment of institutions like the Huronia Regional Centre in Ontario and the Mercer Centre in Alberta (Fritsch et al., 2020; Malacida, 2015). In these institutions, disabled people were incarcerated, isolated, sterilized, violated, and stripped of their rights and autonomy (Malacrida, 2015).

Eugenics research did not adhere to ethics, autonomy, or human rights principles, which justified the dehumanization and systemic oppression of disabled people (Pfieffer, 1994). The use of non-consenting subjects in medical or social research in Canada was standard until the 1946-1947 Nuremberg Trials exposed Nazi medical experimentation (Malaclina, 2015). Following the trials, the World Medical Association began codifying research protocols and informed consent (Malaclina, 2015). However, "invasive and even harmful research on captive or marginal populations could and did continue into the 1960s and early 1970s" (Malacrida, 2015, p.195). Centuries of eugenics research have left a lasting mistrust of academic and medical institutions among disabled people who have historically been targets of research aimed at controlling them (Pfieffer, 1994). This research is embedded in societal, policy, and institutional frameworks, which reinforces skepticism among disabled communities toward care from various institutions (Samson, 2014)

This research has shaped societal norms by framing disability as a biological defect and burden (McLaren, 1990). This discourse presented disabled people as inferior by embedding ableist ideology into public consciousness and policy (McLaren, 1990). Fritsch et al. (2020) posit that "disability has been delineated by the very historical configurations of knowledge and power that depoliticize how it came to be marked as an aberration” (p.11). Eugenics research aligned with dominant ideologies framed disability as an objective medical issue which depoliticizes discourse and reinforces societal norms (Stote, 2015). The research defines what is 'normal' or 'healthy' using a medical lens to justify its legitimacy politically and prevent broader discussions about ableism and societal barriers (Fox, 2021).

Eugenics research influenced public policy and legitimized stereotypes and exclusionary practices (McLaren, 1990). Laws like the Alberta Sterilization Act of 1928 institutionalized the belief that disabled people were unfit for societal participation (Disability Injustice). Institutions like the Michener Centre were established to warehouse disabled people under oppressive conditions and demonstrated how policies codified disability as a threat needing management (Malacrida, 2015). These policies not only reflected societal beliefs but actively shaped public opinion using eugenics research to justify segregation and denial of rights and autonomy (McLaren, 1990). By presenting disability as a defect that needed to be eliminated, eugenics research successfully positioned disabled people as societal burdens and legitimized exclusionary stereotypes and policies (Stote, 2015). Even after discrediting early research like Goddard's feeble-mindedness test, small groups of reformers successfully lobbied at political and grassroots levels while drawing on discredited eugenics research (Malacrida, 2015).

The long-term consequences of this research significantly affect disabled people today (Yergeau, 2013). While Alberta's Michener Centre no longer warehouses abused populations subject to forced sterilizations and nonconsensual experimentation, it continues to operate under Michener Services, admitting disabled people into both newly built group homes and old wards (Malacrida, 2015). This example shows how deinstitutionalization often just meant relocation to jails, nursing homes, or boarding houses (Fritsch et al., 2020). Eugenics research still influences the medical model, which prioritizes "curing" disability over inclusive social services (Ben-Moshe, 2020). Canada's legacies of eugenics and institutionalization persist in modern discourse and interventions (Fritsch et al., 2020). Although state violence may not be as visible and routinized as in the past, violence and control remain ingrained in society (Malacrida, 2015).

Eugenics research has been amplified through media to shape public perceptions and interactions with disabled people by reinforcing the view of disability as a threat needing "fixing" (McLaren, 1990). Media outlets popularized eugenics discourse by portraying disabled people as societal threats through various channels (Fleischer & Zames, 2011; Fritsch et al., 2020). Even as disability discourse shifted towards disability justice, "damaged-centred" research continues to emphasize deficits in the media's representation of disabled people (Tuck, 2009). Using eugenics rhetoric, Premier David Eby announced in September 2024 an expansion of involuntary care for individuals with brain injury, mental illness, and addiction under the Mental Health Act (Government of British Columbia, 2024a; 2024b). Along with the involuntary institutionalization and forced treatment of disabled people, Eby has announced the expansion of psychiatric beds on the grounds of correctional facilities (CMHA, British Columbia, 2024). Media is reinforcing ableist stereotypes, and government policy is framing disabled people as burdens needing removal from society by masking eugenics practices behind policies that claim to provide care (CMHA British Columbia, 2024).

Take a look below at one of the facilities that will be expanding to include hundreds more psychiatric hospital beds for involuntary treatment. Who wouldn’t feel completely cozy and at ease being forcibly treated at a PRISON. Not mentioned in this letter are the linkages between disability and incarceration.

By framing disability as a defect, eugenics established a vocabulary that permeated public discussions about worth and social value (Dorr, 2006). Obscured by discourses of care, benevolence, or safety, this narrative allowed ableist ideologies to embed themselves in societal attitudes and institutional practices (Fritsch et al., 2020). Eugenics research actively constructed biases by labelling certain bodies and minds as deficient. As Yergeau (2013) argues, "theories are about power and denying power" (p.11), highlighting how eugenics research intersects with medicalization, imperialism, slavery, racism, and neoliberalism, which are all tied into white supremacy, capitalism, and colonialism (Tuck, 2009; Fritsch et al., 2020). Eugenics research shaped societal views and influenced institutional approaches to disability by establishing behaviours of surveillance control and power in everyday interactions, public policies, and the broader social system (Stephens & Cryle, 2017; Yergeau, 2013).

As I write this, I’m thinking of survivors of psychiatric institutions; those placed in involuntary treatment within carceral facilities due to social systems that continually fail them; those who sought care voluntarily only to be abused; disabled people quietly swept into long-term care facilities; disabled people who are being silenced and harmed amidst the pandemic; and all those I have neglected to name. I’m thinking of folks who will continue to be harmed by the absolute garbage that is eugenics research. I’m asking myself in what ways have I internalized ableism? In what ways do I reinforce ableism in my language, work, school friendships, values, and politics?

There’s been a lot of academic speak in this letter. A summary is provided below:

To summarize:

Eugenics research framed disability as a defect and justified exclusion, control and violent principles

A handful of prominent eugenics actors, such as Goddard and MacMurchy, promoted and widely expanded practices of sterilization and institutionalization targeting disabled people, MAD people, Indigenous peoples, and racialized populations. (that being said, this has disseminated beyond academic research and seeped into the fabric of our society. it exists within us internalized).

Eugenics research influenced public policy (e.g. Alberta Sterilization Act) and embedded ableist ideologies, which created lasting mistrust among disabled communities

Modern policies like the expansion of involuntary care in British Columbia are rooted in eugenics principles under the guise of “care”

Media and policy continue to depict disability as a societal burden, reinforcing exclusionary stereotypes

The legacy of eugenics connects to broader systems of colonialism, capitalism, and white supremacy, embedding control and surveillance in societal attitudes and practices toward disability.

References

Ben-Moshe, L. (2020). Decaracerating disability: Deinstitutionalization and prison abolition. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctv10vm2vw

CMHA British Columbia. (2024). Involuntary care and its implications for mental health. https://bc.cmha.ca/news/involuntary-care-in-bc/

Dorr, G. M. (2006). Defective or disabled?: Race, medicine, and eugenics in progressive era Virginia and Alabama. The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, 5(4), 359–392. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537781400003224

Fleischer, D., & Zames, F. (2011). Disability and the Media in the 21st century. In D. Papademas (Ed.) Human Rights and Media (Studies in Communications, Vol. 6, pp. 181-218), Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0275-7982(2011)0000006012

Fox, J. (2021). Re-writing the “rules of engagement”: Using critical reflection to examine ableist social work practice. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 33(1), 44–54. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol33iss1id822

Fritsch, K., Monaghan, J., & vander Meulen, E. (Eds.). (2020) Disability injustice: Confronting criminalization in Canada. UBC Press.

Government of British Columbia. (2024a). Mental Health Act. Gov.bc.ca. https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96288_01#section34

Government of British Columbia. (2024b, September 15). BC Gov News. Gov.bc.ca. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2024PREM0043-001532

Kattari, S. K., Ingarfield, L., Hanna, M., McQueen, J., & Ross, K. (2019). Uncovering issues of ableism in social work education: A disability needs assessment. Social Work Education, 39(5), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1699526

Malacrida, C. (2015). A special hell: Institutional life in Alberta’s eugenic years. University of Toronto Press. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/10.3138/9781442620490

McLaren, A. (1990). Our own master race: Eugenics in the history of Canada. The Canadian Historical Review, 71(1), 3-23.

Pfeiffer, D. (1994). Eugenics and disability discrimination. Disability & Society, 9(4), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599466780471

Samson, A. (2014). Eugenics in the community: gendered professions and eugenic sterilization in Alberta, 1928-1972. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, 31(1), 143–163. https://doi.org/10.3138/cbmh.31.1.143

Stephens, E., & Cryle, P. (2017). Eugenics and the normal body: The role of visual images and intelligence testing in framing the treatment of people with disabilities in the early twentieth century. Continuum, 31(3), 365–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2016.1275126

Stote, K. (2015). An act of genocide: Colonialism and the sterilization of Aboriginal women. Fernwood Publishing.

Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409-429.

Yergeau, M. (2013). Addressing ableism in academic research: Voices from the margins. Disability Studies Quarterly, 33(4), 11-27.